Teacher Portal

Investigation 1: Background and Assigned Reading

Background Reading Overview

The Background Reading section provides all scientific content for Investigation 1. Each major topic is clearly labeled with its heading. Teachers may skim or read the content in full before class to gain an overview of the developmental concepts that students will explore in Human Prenatal Development Investigation 1.

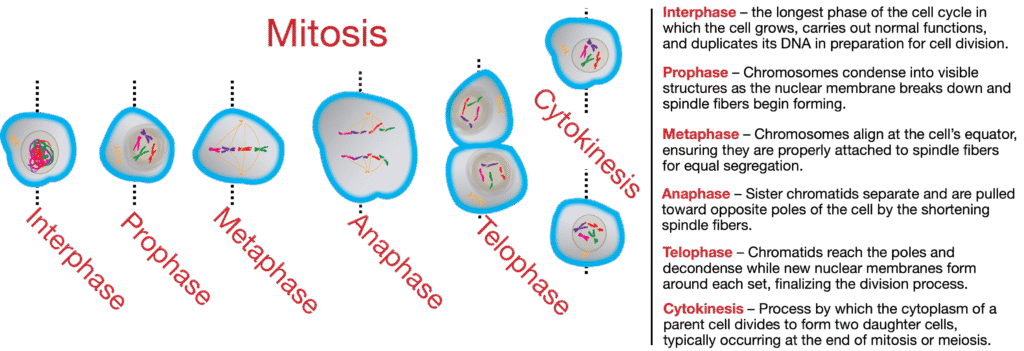

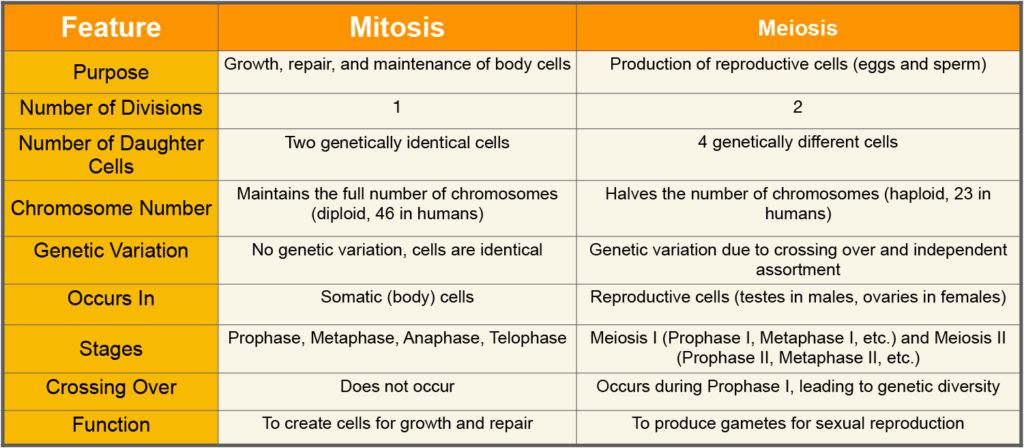

Mitosis and Growth

Mitosis is cell division for growth and repair. It is responsible for the growth of an organism and the repair of injured body tissues. Mitosis produces two identical daughter cells with the same number of chromosomes as the original parent cell.

Mitosis occurs in somatic (body) cells. Interphase, prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase are the five main phases of the cell cycle. Each phase plays a specific role in the division and duplication of the cell’s nucleus and chromosomes.

Check Your Understanding

Q: What is the purpose of mitosis?

A: It produces new cells for growth, development, and repair in the body.Q: How are the daughter cells produced by mitosis similar to the original parent cell?

A: They are genetically identical and have the same number of chromosomes as the parent cell.Q: Name two processes in the human body that rely on mitosis.

A: Growth and healing of wounds rely on mitosis.Q: In which type of cells does mitosis occur?

A: Mitosis occurs in body cells, also called somatic cells.Q: What might happen if mitosis did not occur properly in a wound?

A: The wound might not heal properly, leading to infection or tissue damage.

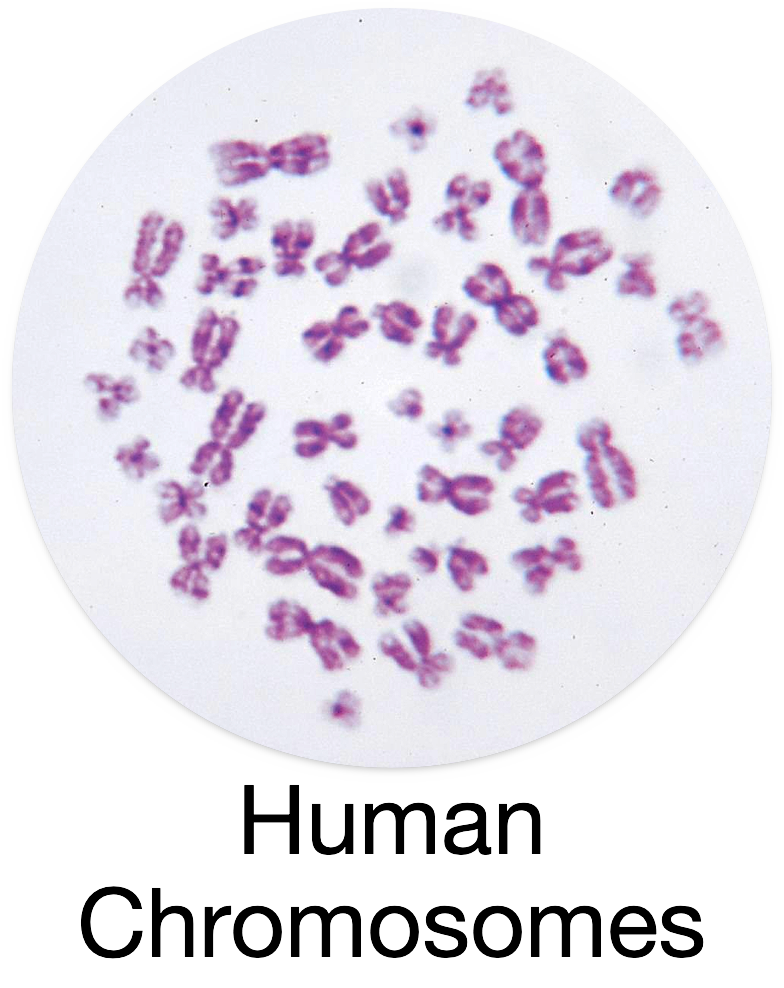

Human Chromosomes

Inside every human cell is a structure called the nucleus. This is where your DNA is stored. DNA holds all the information that makes you who you are—your hair color, height, eye shape, and so much more.

DNA is tightly coiled into structures called chromosomes. Humans normally have 46 chromosomes in each body cell. These chromosomes come in pairs—23 from your mother and 23 from your father.

Fun Fact

If all the DNA from just one of your cells was stretched out, it would be about 6 feet long—but it’s so thin you’d need a microscope to see it!

Q: Where is DNA found in a human cell?

A: DNA is found inside the nucleus of the cell.Q: How many chromosomes does a human body cell have?

A: A human body cell has 46 chromosomes.Q: What is the relationship between DNA and chromosomes?

A: Chromosomes are made of tightly coiled DNA.Q: What’s something interesting about the length of DNA in one cell?

A: If uncoiled, the DNA in one cell would be about 6 feet long.Q: How do we get our 46 chromosomes?

A: We inherit 23 chromosomes from each parent—one set from the mother and one from the father.

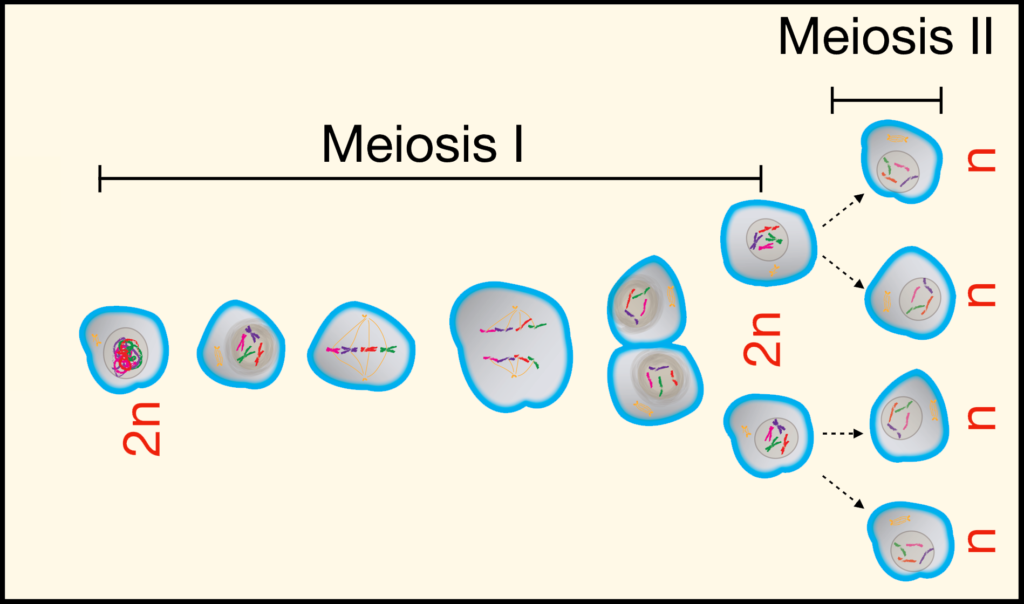

Meiosis and Reproduction

Meiosis is a special type of cell division that makes reproductive cells—egg and sperm. These cells are different from all other cells in your body.

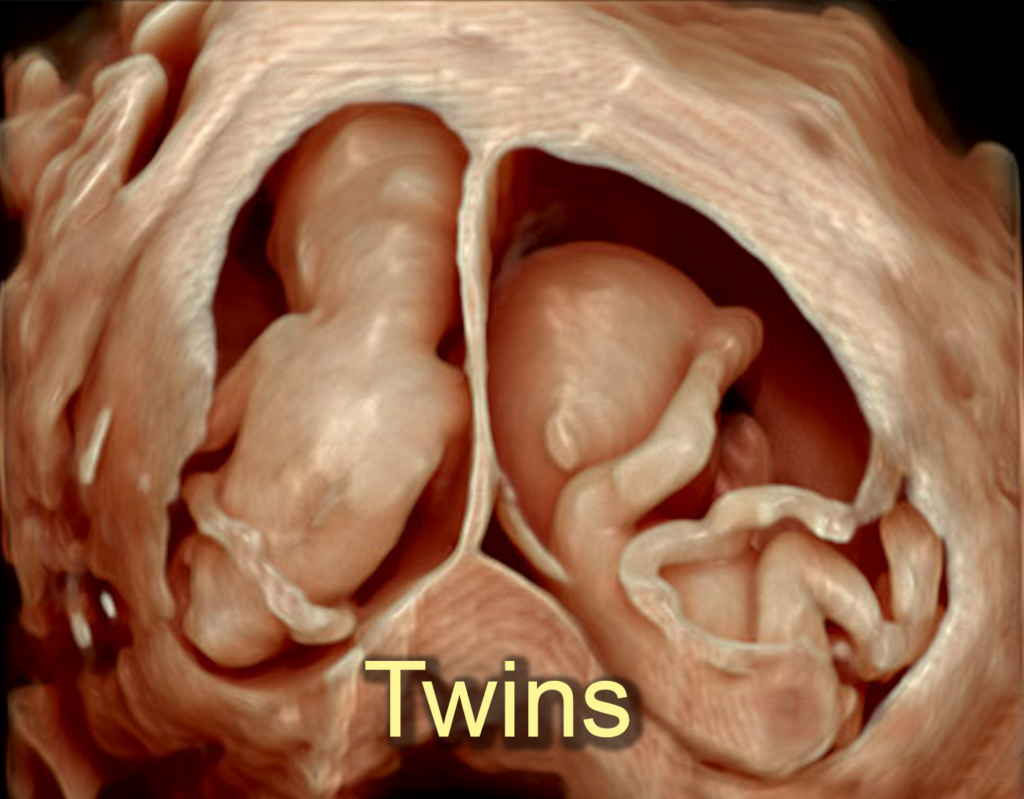

When meiosis happens, the number of chromosomes is cut in half. This way, when the egg and sperm join during fertilization, the baby gets the correct number of chromosomes—46!

Check Your Understanding

Q: What is the purpose of meiosis?

A: Meiosis creates reproductive cells with half the usual number of chromosomes.Q: What kinds of cells are made by meiosis?

A: Egg and sperm cells, also called gametes.

Menstrual Cycle and Reproduction

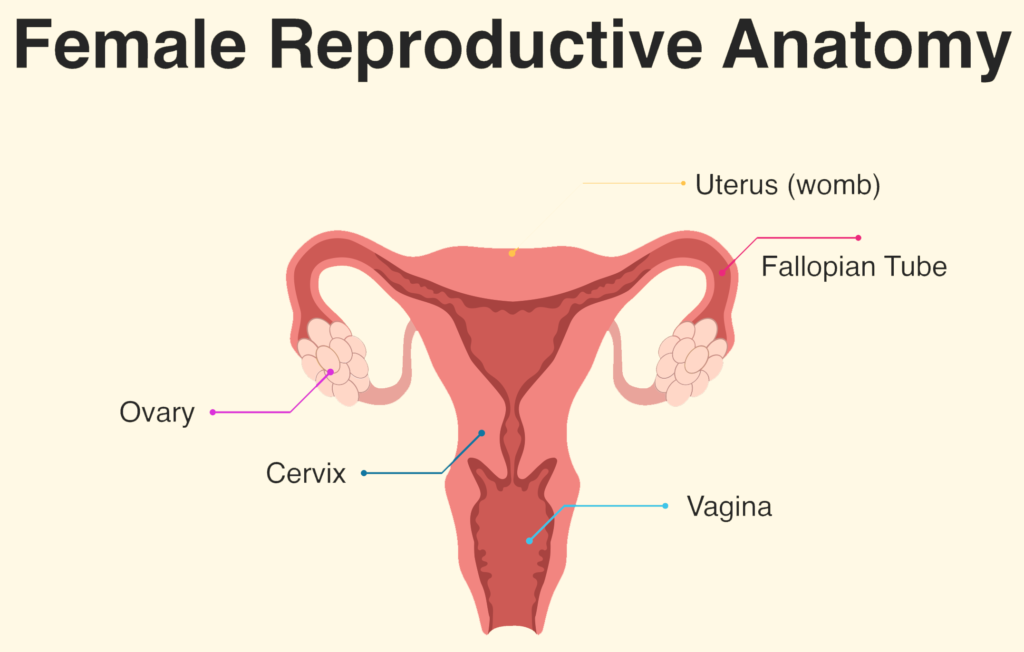

To understand fertilization, you need to know about the menstrual cycle. The menstrual cycle happens roughly every month in a female’s body to prepare for a possible pregnancy.

The human menstrual cycle typically begins during puberty, which is when a female’s body starts to develop and change. The usual age for this to start is around 12 years old, but it can happen anytime between 9 and 16 years old.

Once the menstrual cycle starts, it generally continues each month until a person reaches menopause, which usually happens between the ages of 45 and 55, when the menstrual cycle stops permanently.

The menstrual cycle usually lasts about 28 days but can be a little shorter or longer. Here’s a simple overview:

- Days 1–5: The cycle begins with menstruation when the lining of the uterus (the womb) sheds if no fertilization happened in the previous cycle. This lining exits the body as what we call a “period.”

- Days 6–14: The body starts to prepare for the next cycle. A new egg cell begins to grow and mature in the ovary. Meanwhile, the lining of the uterus starts to thicken again, getting ready for a fertilized egg to attach.

- Around Day 14 (Ovulation): This is the ovulation phase. The egg leaves the ovary and travels down the fallopian tube, where it might meet a sperm. This is the time when fertilization is most likely to happen because the egg is ready to be fertilized.

- Days 15–28: If the egg is not fertilized, it breaks down, and the uterus lining gets ready to shed again, starting a new cycle.

Fertilization can happen if sperm enters the female body during or close to the time of ovulation (around Day 14). Sperm cells swim through the uterus to reach the fallopian tube, where they might meet the egg. When one sperm manages to join with the egg, it fertilizes it, and the egg becomes a zygote, the very first stage of a new human life.

After fertilization, the zygote travels to the uterus and attaches to the thickened lining. This is where it will continue to grow and develop into a baby over the next nine months.

In summary:

- Fertilization can only occur if sperm meets the egg when it’s in the fallopian tube, which happens around Day 14 of the menstrual cycle.

- If fertilization doesn’t happen, the egg will eventually break down, and the cycle starts again.

Fertilization

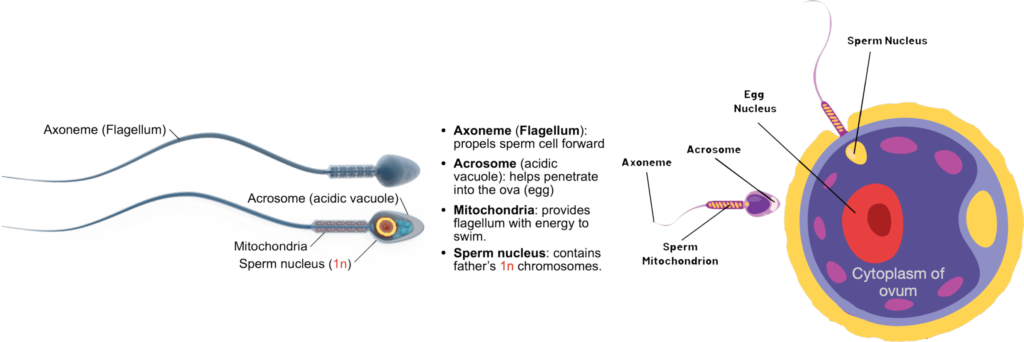

Fertilization is the process where a sperm cell from the father combines with an egg cell from the mother to form a new, genetically unique individual. Only males can produce sperm cells, and only females can produce egg cells (also called ova). Meiosis is required to form both types of gametes (sex cells).

Both sperm and egg cells are haploid, meaning they each have only half the number of chromosomes needed to make a complete set. A complete set of chromosomes in humans is 46, but each haploid cell has only 23 chromosomes.

The Role of Sperm and Egg Cells

Sperm Cell: The sperm cell is produced in the father’s body and carries 23 chromosomes. It is very small and has a tail called a flagellum, which helps it swim toward the egg cell.

Egg Cell: The egg cell (or ovum) is produced in the mother’s body and has 23 chromosomes. It is much larger than the sperm cell and is filled with nutrients to help the developing embryo grow in its early stages.

The Process of Fertilization

When the sperm cell reaches the egg cell, they combine. This is called fertilization. The sperm’s 23 chromosomes and the egg’s 23 chromosomes join together, making a complete set of 46 chromosomes. This new cell is called a zygote.

The zygote has all the genetic information it needs to develop into a new human. It will continue to divide and grow into an embryo and, eventually, a baby.

Why Is Fertilization Important?

Fertilization is important because it combines genetic material from both parents. This means that the baby will have traits from both the father and the mother, like eye color, hair color, and other characteristics. The combination of chromosomes from both parents also makes every person unique from fertilization onward.

Check Your Understanding: The Menstrual Cycle

- Q: What is the purpose of the menstrual cycle?

A: It prepares the body for pregnancy by thickening the uterus lining. - Q: What happens during menstruation?

A: The uterus sheds its lining if no fertilization occurs, resulting in a period. - Q: When does ovulation usually occur?

A: Around Day 14 of the cycle, when the egg is released from the ovary. - Q: What happens if an egg is not fertilized?

A: It breaks down, and the menstrual cycle restarts. - Q: How does the cycle change with age?

A: It starts during puberty (around age 12) and ends with menopause (around age 50).

Check Your Understanding: Fertilization

- Q: What is fertilization?

A: It’s when a sperm cell and egg cell combine to form a zygote. - Q: How many chromosomes does each gamete have?

A: Each has 23 chromosomes. - Q: What is a zygote?

A: It’s the first cell formed after fertilization with 46 chromosomes. - Q: Why is fertilization important?

A: It combines genetic material from both parents to create a unique individual. - Q: Where does fertilization usually occur?

A: In the fallopian tube.

The Placenta: Structure, Function, and a Rare Exception

The placenta is a temporary organ that forms during pregnancy and connects the developing baby to the mother. It supports the exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and wastes between maternal and fetal bloodstreams. Importantly, the placenta acts as a selective barrier. While it allows many necessary molecules to pass between mother and fetus, it normally prevents the transfer of whole cells, including red blood cells and most immune cells.

Because of this selective design, the placenta protects the developing baby while still allowing essential materials to move in and out.

Teacher Note: Maternal Microchimerism

(Not part of the student version of the BR)

Although the placenta normally blocks the passage of whole cells, research has shown a rare but important exception. A very small number of fetal-derived cells can occasionally cross into the mother’s bloodstream during pregnancy—a phenomenon called maternal microchimerism. These cells are extremely few in number and do not change the placenta’s primary role as a selective barrier.

Microchimerism can occur at any stage of pregnancy, though it is most common during early placental formation and again near delivery. Some fetal-origin cells may persist in the mother’s body for many years—sometimes for life. If a woman experiences more than one pregnancy, small numbers of cells from each child may remain in her body.

Scientists are still studying the roles these cells may play in maternal health, immune function, and tissue repair. This information is provided for your scientific background only and is not part of the student learning objectives. Broader moral and theological considerations related to this discovery appear in the Faith & Reason Teacher resources for HPD3.

Check Your Understanding

1. Q: What are two important jobs of the placenta?

A: Supplying oxygen and nutrients to the fetus and removing fetal wastes.

2. Q: Why can’t most large structures, like blood cells, cross the placenta?

A: Because the placenta acts as a selective barrier, allowing only certain molecules to pass.

3. Q: What is the rare exception called when a few fetal cells enter the mother’s bloodstream?

A: This rare event is called maternal microchimerism.

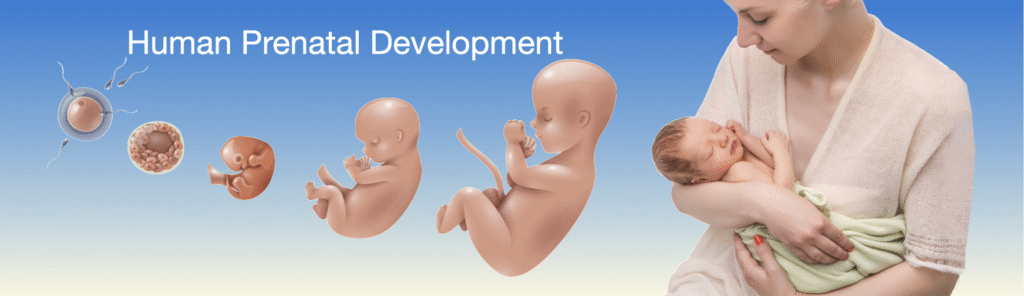

First Trimester: Embryonic Development

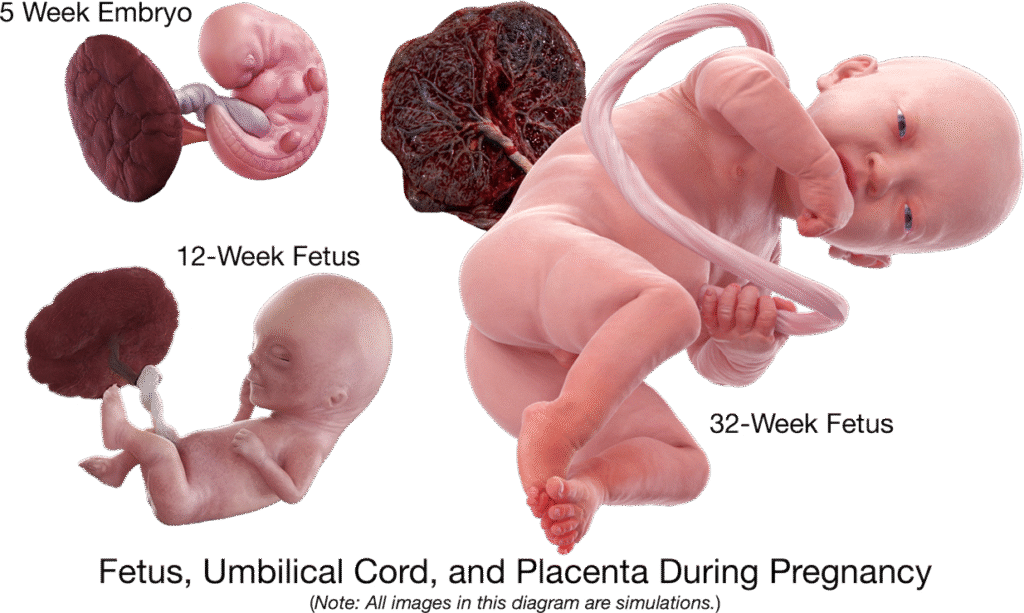

The first trimester of pregnancy is the most critical time for a developing baby. It spans from week 1 to week 12. During this time, the fertilized egg becomes a tiny embryo and quickly begins to grow and change.

Here are some of the most important milestones in the first trimester:

- Weeks 1–2: These are the weeks of fertilization and implantation. The fertilized egg travels down the fallopian tube and attaches to the uterus lining.

- Week 3: The zygote begins dividing and forms a tiny ball of cells. This is the beginning of embryogenesis.

- Week 4: The embryo forms a structure called the neural tube, which will become the brain and spinal cord.

- Week 5: The heart begins to form and will start to beat.

- Weeks 6–8: Major organs begin developing, including the lungs, stomach, and liver. Limb buds appear, which will become arms and legs.

- Weeks 9–12: The embryo becomes a fetus. Facial features become more defined, and tiny fingers and toes form.

Check Your Understanding: First Trimester

- Q: What important organ starts beating during the first trimester?

A: The heart begins to beat around week 5. - Q: What is the neural tube and why is it important?

A: The neural tube will develop into the baby’s brain and spinal cord. - Q: When does the embryo officially become a fetus?

A: Around week 9, when major organ systems are formed. - Q: What begins to form that will later become the arms and legs?

A: Limb buds appear during weeks 6 to 8. - Q: What is one sign of growth seen in the face?

A: Facial features become more defined in weeks 9–12.

Second Trimester: Fetal Development

A developing embryo is typically referred to as a fetus after the 10th week of pregnancy. Thus, the entire second and third trimester of pregnancy may be referred to as fetal development.

The second trimester is the period from week 13 to week 26 of pregnancy. This is a time of rapid growth and development for the baby, and it’s often when the mother starts to feel the baby move. Let’s go through what happens step by step!

Weeks 13–16: Growth and Movement

- The baby continues to grow quickly and now looks more like a tiny human. The face becomes more detailed, with eyebrows, eyelashes, and even hair starting to form.

- The baby’s bones are hardening, and the muscles are developing more, allowing the baby to move its arms, legs, and even make little fists.

- By the end of this period, the baby is about the size of an avocado (about 4 to 5 inches long).

Weeks 17–20: Senses and Reactions

- The baby’s nervous system (brain and nerves) continues to develop, and it starts to react to light and sound.

- The baby’s ears are fully formed, so it can even start hearing sounds like the mother’s heartbeat and voice!

- A layer called vernix caseosa (vernix for short) forms on the baby’s skin to protect it. The skin itself is still very thin.

- At this stage, the baby is around the size of a banana, and the mother may feel kicks and movements for the first time.

Weeks 21–24: Organ Development and Chances of Survival

- The baby’s lungs and digestive system are developing, although they still have more growing to do before they’re ready to work on their own.

- The baby is practicing breathing by inhaling small amounts of amniotic fluid, which helps develop the lungs.

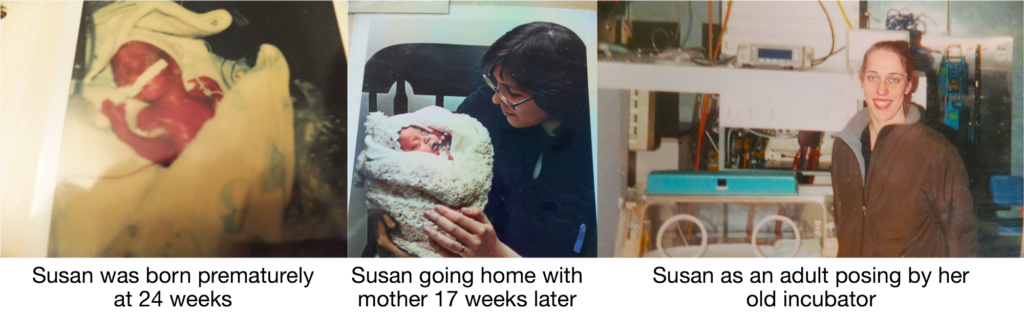

- By week 24, the baby is about the size of an ear of corn. This is also when the baby’s chances of survival if born early, start to improve. Babies born at this stage are called premature, and while they would need special medical help, they have a small chance of survival.

Weeks 25–26: Improving Survival Chances

- During these weeks, the baby’s lungs continue to develop, and the air sacs that are important for breathing start to form. The baby is getting better prepared for life outside the womb.

- The baby also begins to put on more fat, which helps regulate body temperature after birth.

- By the end of the second trimester, the baby is around the size of a cabbage and weighs about 1.5 to 2 pounds.

Survival Chances During the Second Trimester

- Before Week 24: If a baby is born earlier than this, the chances of survival are very low because the lungs and other organs are not developed enough.

- Week 24: Survival rates improve but are still low. With special medical care, a baby born at this stage has a 50% chance of survival.

- Week 26: The survival chances are even better, with some babies having about an 80% chance of surviving if born at this point, though they would still need to be in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

In summary, the second trimester is all about the baby growing bigger, moving more, and developing important organs and systems. As time passes, the baby’s chances of surviving outside the womb improve, especially as it gets closer to the third trimester.

Check Your Understanding

- Q: When does the second trimester occur?

A: From Week 13 to Week 26 of pregnancy. - Q: What protective layer forms during this stage?

A: The vernix caseosa, a waxy coating that protects the skin. - Q: When can the baby start hearing sounds?

A: Around Week 18, when the ears are fully formed. - Q: What is the survival chance if born at Week 24?

A: About 50%, with intensive medical support. - Q: How does the baby practice breathing?

A: By inhaling small amounts of amniotic fluid.

Third Trimester: Growth and Birth

The third trimester marks the final stage of pregnancy and includes the period from week 28 through birth (typically around 40 weeks). During this time, the fetus undergoes significant growth and prepares for life outside the womb.

In this trimester:

- The brain continues to develop rapidly, forming more neural connections and increasing in complexity.

- The lungs mature, producing surfactant, a substance that helps the baby breathe after birth.

- The fetus gains weight quickly, developing fat stores to help regulate body temperature after birth.

- Movements become stronger, and the baby can often be felt shifting, kicking, or stretching.

- The fetus begins to respond to sounds and light and may even recognize the voice of the mother or father.

- Braxton Hicks contractions, also known as practice or false labor contractions, can start as early as the second trimester, but most women notice them in the second or third trimester.

Check Your Understanding:

- Q: What weeks are considered the third trimester?

A: Weeks 28 through 40 (birth). - Q: What important substance do the lungs produce during this trimester?

A: Surfactant, which helps the baby breathe after birth. - Q: Why does the fetus gain fat during the third trimester?

A: To help regulate body temperature after birth. - Q: What are Braxton Hicks contractions?

A: Practice contractions that prepare the body for labor. - Q: What position is the fetus usually in by the end of the third trimester?

A: Head-down position in preparation for birth.

Essential Concepts

Modeling the Miracle: How Human Life Develops

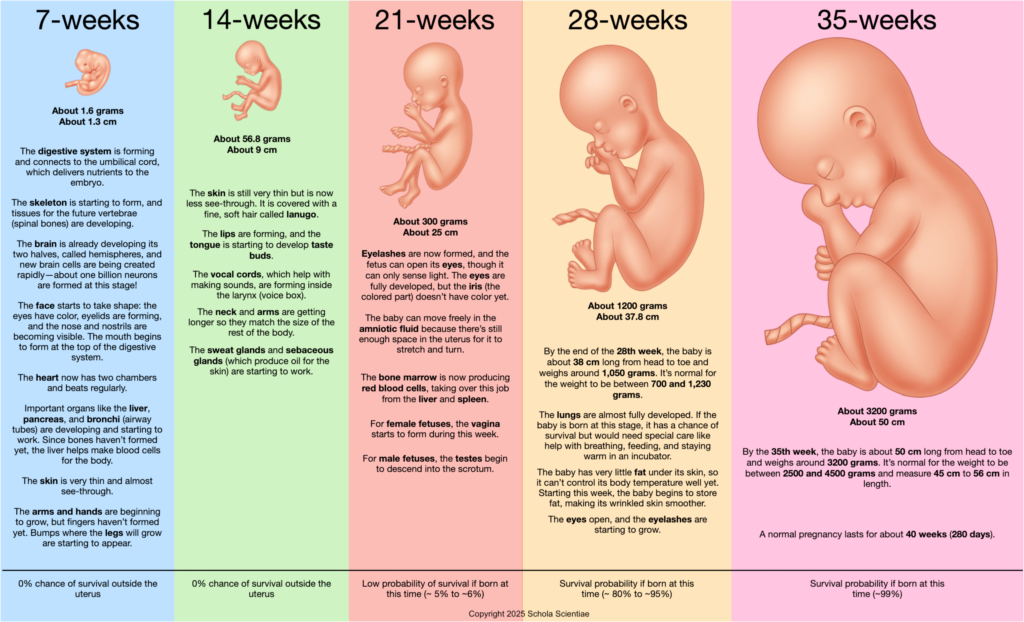

1. Data Interpretation

What patterns of growth and change occur between Weeks 7, 14, 21, and 28 of prenatal development? How do these patterns illustrate fetal growth overall?

As the weeks progress, fetal mass and length increase rapidly.

Organs and limbs form early, then mature and become functional.

Each developmental stage builds upon the previous one, accelerating in complexity and coordination.

Key Idea: Fetal development follows a predictable sequence, and each stage prepares for the next.

2. Critical Thinking

Why do chances of survival outside the womb increase as the fetus develops? How do changes in organs and systems support this?

Organs become structurally complete and begin functioning.

Lung, heart, and brain development allows breathing, circulation, and regulation.

Improved movement and coordination indicate maturing neural control.

Key Idea: Survival improves because the fetus becomes more physiologically independent.

3. Real-World Application

How can knowledge of developmental milestones improve prenatal care and support healthy birth outcomes?

Understanding milestone timing helps detect abnormalities early.

Healthcare professionals can offer targeted interventions when needed.

Expectant parents receive reassurance and concrete developmental expectations.

Key Idea: Knowledge of prenatal milestones strengthens medical care, supports families, and promotes healthy outcomes.

Investigation 1: Chromosomes and Inheritance

1. Data Interpretation

Examine the karyotype images of a human male and a human female. What differences do you observe in the sex chromosomes, and how do these differences support the concept of genetic inheritance?

When comparing the karyotypes, you’ll notice that both individuals have 22 pairs of autosomes that are identical. However:

The female karyotype shows XX,

The male karyotype shows XY, with the Y chromosome significantly smaller.

These patterns confirm that sex is determined by the presence or absence of the Y chromosome, which carries genes responsible for male development.

Key Idea: Sex determination is genetically based. The Y chromosome—though smaller—contains specific genes that direct male development, while the absence of the Y chromosome leads to female development.

2. Critical Thinking

Considering that the Y chromosome is smaller and contains fewer genes, why do you think this difference exists, and what might it mean for the expression of genetic traits?

The size difference likely reflects the Y chromosome’s evolutionary specialization, losing many genes over time.

The X chromosome, in contrast, carries many genes unrelated to sex.

Because males only have one X chromosome, they lack a second copy that might “cover” defective genes.

This explains why males have a higher risk of X-linked genetic disorders such as colorblindness or hemophilia.

Key Idea: Genetic differences between males and females are rooted in chromosome structure. Males’ single X chromosome makes some traits more vulnerable to mutation effects.

3. Real-World Application

How can understanding karyotypes and the differences between male and female chromosomes be applied in medical practice and genetic research?

Karyotyping helps detect chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome).

It guides genetic counseling, prenatal screening, and diagnosis of inherited disorders.

It provides insights for personalized medicine, especially when sex-linked traits affect disease risk.

Key Idea: Karyotype analysis is a powerful diagnostic tool, helping clinicians detect chromosomal conditions early and support families with accurate genetic information.

Investigation 2: Fetal Growth Over Time

1. Data Interpretation

What patterns do you see when you compare fetal length and mass at different weeks of development?

Length and mass both increase throughout gestation, but not at the same rate.

Growth is relatively gradual early in the first trimester, then accelerates in the second and early third trimesters.

Graphs and tables show that each developmental “jump” builds on earlier tissue and organ formation.

Key Idea: Growth is orderly and patterned, not random. The fetus follows a predictable trajectory of increasing size and complexity.

2. Critical Thinking

Why is it important to distinguish between normal variation in growth and signs of growth restriction or over-growth?

Not every fetus will match the “average” curve exactly, but large deviations can signal potential problems.

Too little growth may indicate nutritional issues, placental problems, or underlying medical conditions.

Excessive growth can also create risks, such as delivery complications or metabolic concerns.

Key Idea: Understanding “normal” growth helps teachers and students interpret graphs realistically and recognize why clinicians monitor fetal size so carefully.

3. Real-World Application

How do healthcare professionals use growth charts and measurements during prenatal care?

Ultrasound measurements of length, head circumference, and estimated mass are plotted against growth charts.

These data help clinicians decide whether additional testing, nutritional counseling, or closer monitoring is needed.

Parents receive concrete, visual feedback about how their baby is developing.

Key Idea: Fetal growth data guide real clinical decisions and provide reassurance—or early warning—during pregnancy.

Investigation 3: Placenta, Support Systems, and Maternal Health

1. Data Interpretation

What do models and diagrams show about how the placenta and umbilical cord support fetal life?

The placenta anchors to the uterine wall and connects to the fetus through the umbilical cord.

Separate maternal and fetal blood supplies allow exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and wastes without mixing blood directly.

Diagrams highlight the close contact between maternal and fetal capillaries in the chorionic villi.

Key Idea: The placenta functions as a temporary life-support system, performing the jobs of lungs, digestive system, and kidneys for the fetus.

2. Critical Thinking

Why is maternal health so important for placental function and fetal development?

Substances the mother takes in—food, medications, alcohol, nicotine, and some drugs—can cross the placenta.

Poor maternal nutrition or reduced blood flow can limit the oxygen and nutrients available to the fetus.

Certain infections and toxins can also reach the fetus through the placenta, especially early in development.

Key Idea: The placenta does not completely “shield” the fetus; it also transmits the effects of the mother’s choices and environment.

3. Real-World Application

How does understanding placental function guide recommendations for healthy pregnancies?

Explains why physicians advise balanced nutrition, avoiding alcohol, tobacco, and non-prescribed drugs, and careful use of medications.

Helps parents understand why conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, or infections must be managed closely during pregnancy.

Provides a scientific basis for public-health messages about protecting prenatal life.

Key Idea: Knowledge of placental exchange supports responsible decision-making and compassionate care for both mother and child.

Investigation 4: Third Trimester & Birth Preparation

1. Data Interpretation

What key changes occur in organ systems during the second and third trimesters, and how do these changes prepare the fetus for life outside the womb?

Lungs develop alveoli (air sacs) and begin producing surfactant, preparing the fetus for breathing.

Brain undergoes rapid growth in size, structure, and neural connections.

Heart becomes stronger and more efficient, supporting increased metabolic demands.

Overall mass and size increase significantly, preparing the infant for temperature regulation, feeding, and movement after birth.

Key Idea: The second and third trimesters complete the development of major organ systems, enabling the fetus to transition from uterine dependence to newborn independence.

2. Critical Thinking

Why might a baby born at the end of the sixth month (around 24–26 weeks) survive with medical support, while earlier births face much lower survival chances?

By 24–26 weeks, the lungs—though still immature—have reached the earliest stage at which gas exchange is possible.

The nervous system can begin regulating basic reflexes, such as breathing and heart rhythm.

Improved circulation and heart function allow limited physiological stability.

However, earlier than this point, the fetal lungs and brain are too underdeveloped to sustain life, even with medical intervention.

Key Idea: A newborn’s chances of survival depend heavily on lung maturity, neurological development, and circulatory readiness.

3. Real-World Application

How does ultrasound technology help monitor fetal development during the later stages of pregnancy?

Ultrasound provides non-invasive, real-time visualization of fetal size, position, organ development, and amniotic fluid levels.

It helps detect growth delays, placenta placement issues, and structural abnormalities.

It allows parents and healthcare professionals to prepare for safe delivery, including interventions if needed.

Key Idea: Ultrasound technology strengthens prenatal care by allowing early identification of potential concerns and by guiding medical decisions in late pregnancy.

Vocabulary

Teacher Note: The Importance of Scientific Vocabulary: Scientific vocabulary is essential for helping students build precise and confident understanding of complex ideas. Many scientific terms have Latin or Greek origins, which allows them to be used consistently across biology, chemistry, and physical science. Recognizing these roots gives students powerful tools for decoding unfamiliar words and connecting concepts across Investigations. The vocabulary listed here serves as a teacher reference to support lesson planning and discussion. Students will encounter age-appropriate vocabulary directly in the PreLab readings, where key terms are introduced in context so that meaning develops naturally through use rather than memorization.

Amniotic Fluid

The protective liquid surrounding the fetus inside the amniotic sac. It cushions the fetus, regulates temperature, and allows movement for proper development.

Amniotic Sac

The thin, transparent membrane that surrounds the fetus and holds the amniotic fluid.

Chorionic Villi

Finger-like projections extending from the placenta into the uterine wall. They bring fetal blood close to maternal blood for nutrient and gas exchange.

Chromosomes

Threadlike structures in the nucleus made of DNA and protein. Humans have 23 pairs (46 total).

Embryo

The developing human from fertilization through the end of the eighth week of pregnancy.

Fetus

The developing human from the ninth week of pregnancy until birth.

Fertilization

The union of a sperm cell and egg cell that forms a zygote.

Karyotype

A photograph or diagram of an individual’s complete set of chromosomes arranged in pairs.

Meiosis

A special type of cell division that produces sperm and egg cells, each containing half the normal number of chromosomes.

Mitosis

Division of a cell’s nucleus resulting in two identical daughter cells. Responsible for growth and tissue repair.

Placenta

A temporary organ that connects the fetus to the mother. It delivers oxygen and nutrients while removing waste products, without mixing maternal and fetal blood.

Trimester

One of three roughly equal periods of pregnancy, each lasting about 12–13 weeks.

Umbilical Cord

A bundle of blood vessels that connects the fetus to the placenta, carrying oxygen and nutrients to the fetus and removing waste.

Uterus

The muscular organ in a woman’s abdomen where the embryo and fetus develop during pregnancy.

Zygote

The single fertilized cell formed when sperm and egg unite.